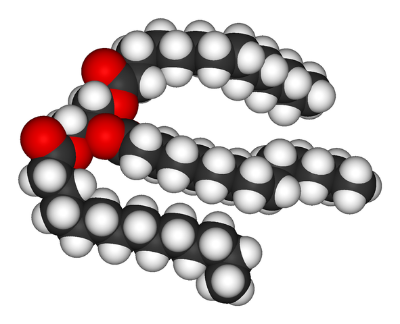

Last week we published a blog on the gut-brain axis, and the various associations between brain health and the gut microbiome. One of the ailments we discussed was depression, which is often studied in mice by inducing early life stress on the mice. One way to do this is by separating mice from their mothers for hours at a time at a young age. The Maternal Separation model, as it is known, causes stress and anxiety in these mice, but more importantly, research has shown that it creates a dysbiosis of their gut microbiomes as well. Many scientists believe the dysbiosis may be implicated in causing some of the stress phenotypes, and so reversing this dysbiosis could have therapeutic value. Researchers from the University College Cork, in Cork Ireland, experimented with N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), like those found in fish oil, in these maternally separated mice, and found they may be important to preventing the dysbiosis. They published their findings in the journal PLoS ONE.

In the study, the researchers separated mice into two groups, one underwent maternal separation, and the other had a normal upbringing. Within each group the mice were separated into two more groups, one that received fish oil supplements and the other that didn’t. Over the course of 17 weeks each groups’ feces were sampled for their microbiomes. The Maternal separation tended to decrease the bacteroidetes to firmicutes ratio of the mice’s microbiome, which has previously been linked to depression in humans. Interestingly, supplementation with the fish oil increased this ratio in those maternally separated mice. In addition, the fish oil also increased the concentration of bacteria that were higher in non-separated mice, such as populations of Rikenella. Finally, the fish oil increased the amount of butyrate producing bacteria, and as we have seen many times before, butyrate and other short chained fatty acids (SCFAs) are often associated with health.

Overall this study showed that fish oil shifted stressed mice’s microbiome to a more natural state, presumably helping them in the process. While the scientists did not directly measure stress levels in these mice to support the microbiome connection, hopefully that will be part of a follow up study. The scientists noted that fish oil is clinically shown to reduce inflammation, and made it a point to connect the stress in the mice to systemic inflammation. Systemic inflammation is also mediated by the microbiome. Indeed, people that have inflammation from IBD, for example, do tend to have more stress and anxiety. In the end, fish oil could make for an interesting prebiotic to shift the microbiome, counteract inflammation, and improve mental health.