The white and brown turkey meat from a Thanksgiving dinner

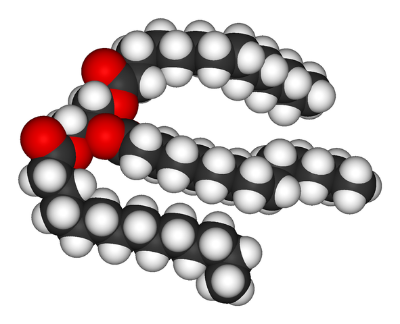

An interesting article from Switzerland was published last week in Nature Medicine. The scientists reported on a new connection between the gut microbiome and metabolic syndrome (i.e. insulin sensitivity, obesity, etc.) Whereas most papers observe microbiome disruption and depletion is associated with obesity, this paper describes a different phenomenon: that mice with depleted microbiomes are metabolically healthier than their untouched microbiome counterparts. As part of the basis for the paper it is important to understand that mammals have two types of fat, brown fat and white fat. Brown fat is associated with exercise, insulin sensitivity, and health, and white fat is associated with insulin resistance and diabetes. Brown fat can actually repopulate white fat in a process called browning, and this transition is healthy.

In the study, the scientists started with either normal mice, germ free mice, or mice that had antibiotics administered to them. They challenged each group of mice with glucose, and noted that antibiotic administration led to improved insulin sensitivity. When they investigated where the glucose was going, they discovered that it was uptaken by white adipose tissue under the skin. Then, they compared the normal mice and antibiotic mice, and observed that the antibiotic mice actually had smaller volumes of fat after the glucose uptake. Interestingly, the fat cells in the germ free and antibiotic mice were smaller and more dense, whereas the normal mice had fewer, larger cells. The researchers then confirmed that browning of fat was occurring in the germ free and antibiotic mice. Finally, when the scientists transplanted the microbiome of normal mice into the germ free mice a reversal of many the above described characteristics occurred. In these mice the fat stopped browning, insulin resistance decreased, and the mice gained weight.

The scientists were able to attribute some of the above phenomena to the release of specific cytokines (molecules that regulate the immune system). This paper, then, adds to the wealth of research that describes the complex but critical interaction between the gut microbiome, the immune system, and metabolic syndrome. Although the relationships between these things is yet to be fully understood, this paper may at least change the way you think about the dark and white meat during Thanksgiving dinner this Thursday.