The Microbiome Podcast has been on a hiatus since June so we wanted to make sure that our first episode back was a good one. Our conversation with Dr. John Cryan from University College Cork in Ireland was very informative and for anyone interested in how the microbiome and the gut may impact the brain during development or in later stages of life, this is a great listen.

Listen to the episode on our website. On iTunes. On Stitcher.

On this week’s episode we discussed:

- (1:06) Our visit to the White House and the Office of Science and Technology Policy’s microbiome initiative.

- (3:30) A paper describing the “microbial cloud” that individuals emit. Read the paper.

- (6:18) A C. diff treatment that ReBiotix received breakthrough designation from the FDA. Read more.

- (9:04) We were joined by Dr. John Cryan.

- (9:20) What is the gut-brain axis?

- (12:00) The importance of the gut-brain axis during early stages of life.

- (13:35) Studies in humans that show how the microbiome may influence brain function. A study from Mike Baley's group on temperament during early childhood.

- (15:20) Psychobiotics.

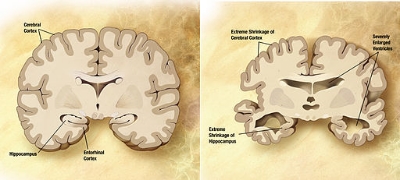

- (22:45) The gut-brain axis in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. A study from Denmark that showed if a person had their vagal nerve removed halved their chances of getting Parkinson’s disease.

- (27:40) Microbiome mediating hunger and a specific hormone called ghrelin.

- (32:40) Research in the Cryan Lab. Read more.

- (37:05) The APC Microbiome Institute at University College Cork. Learn more.

- (41:00) On the aftershow, we discussed our opinions of iPhones and Apple products.