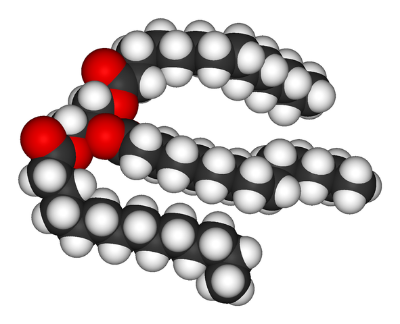

A triglyceride molecule, the main constituent of lard.

Dietary fat comes in many in many different forms, such as saturated fats that come from foods like lard, and polyunsaturated fats that come from foods like fish oil. It is generally believed that saturated fats lead to inflammation and obesity, but that polyunsaturated fats are healthier, and can counteract inflammation and promote healthy metabolism. The role of the microbiome in mediating these effects is still unknown, but is beginning to be elucidated. A team of researchers from Sweden, Belgium and Denmark showed that the lipids themselves alter the microbiome, which induces the characteristic inflammation associated with ingesting saturated fats. Their results were published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

The scientists fed groups of mice identical diets that only differed in the type of fat that was consumed: lard composed of saturated fats, and fish oil composed of polyunsaturated fat. As expected, the group that ate the saturated fat gained weight and had higher fasting glucose than those eating unsaturated fat. When they measured the gut microbiomes of these mice, they discovered that the overall diversity of bacteria were much lower in the mice eating the saturated fat diet. Next, the scientists measured the contents of the blood of the mice and discovered that there were higher levels of bacterial metabolites and bacterial components in the blood of mice eating the saturated fat diet. Using complicated techniques that are beyond the scope of this blog, the researchers were able to trace the inflammation to an increase in specific receptors in the gut that are activated by bacteria from the saturated fat diet, including some specific toll like receptors (TLRs). The scientists conducted a final experiment to show the importance of the microbiota, rather than the diet, in inducing these effects. They transplanted the feces of both groups of mice into new, healthy mice. The mice given the feces of the saturated fat group gained weight, whereas the ones given the microbiomes of the polyunsaturated fat group tended to lose weight.

The scientists believe that diets high in saturated fats upregulate specific immune system receptors that are activated by factors derived from the gut microbiome. Moreover, these factors find their way into the blood much more easily after consuming saturated fat, as opposed to unsaturated fat, so they can easily activate these receptors. After activation the factors lead to inflammation and obesity. Overall, this research explains one of the reasons why polyunsaturated fats are healthier than saturated ones. We know It’s not often anyone is faced with the choice between fish and lard, but after reading this study we recommend our readers go with the fish.