CT scan showing Crohn's disease in the fundus of the stomach

Crohn’s disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease that is characterized by an autoimmune response in the colon. It is generally thought that the bacteria in the gut elicit this immune response and cause the disease. In otherwords, Crohn’s is caused by a shift in the microbiome from a healthy state, to a dysbiotic one, although the ultimate cause of the disease is still unknown. The standard of care for Crohn’s in adults is combinations of immunosuppressive drugs, although in children this is not normally recommended. Instead, children take either a prescribed diet, normally something like Soylent that involves only essential nutrients, or antibiotics. Scientists from UPenn recently monitored the microbiomes of children with Crohn’s that were put on various courses of treatment, as well as the progression of the disease. They discovered the changes that occurred in the microbiome that yielded a therapeutic response, and many new associations between the microbiome and Crohn’s disease. They published their results in Cell Host and Microbe.

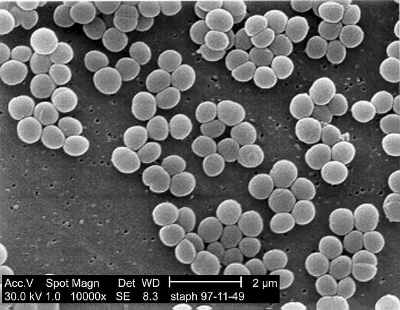

The scientists measured the microbiomes and inflammatory markers of 90 children before and after entering therapy for Crohn’s: 52 taking anti-TNF (an immunosuppressant), 22 taking the enteral nutrition exclusively (i.e. something like soylent), and 16 taking the enteral nutrition along with any other food they wanted. The scientists also took samples from 26 healthy children. They discovered that of the 45 most abundant bacteria in each child, 14 were different between the Crohn’s children and the healthy children. These included bacteria such as Prevotella and Odoribacter that were largely absent from the Crohn’s group, and Streptococcus, Klebsiella, and Lactobacillus that were in higher abundances in the diseased group. Overall diversity was also higher in healthy patients compared to those with Crohn’s. The researchers also discovered that high levels of fungi, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in the stool were high associated with Crohn’s. When the researchers monitored the response of Crohn’s patients to treatment they saw that in many patients the microbiome shifted rapidly to a healthier state, with less inflammation, within a week of treatment for all three therapies involved.

This study helped further define the dysbiosis that is associated with Crohn’s disease, as well as demonstrate how this dysbiosis is altered using treatment. It was especially useful that treatment naïve children were used in the study, as many adult studies are unable to remove confounding variables of various previous courses of treatments. IBD is a difficult disease to study because of its complexity, but this study supports the hypothesis that a dysbiosis is at the root of the problem.