Most people experience acne at some point in their life, and the AMI has discussed the microbiome’s role in this skin condition many times in our blog and podcasts. Cutaneous inflammation is observed in people with acne, as well as increased amounts of the Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) bacteria. However, a recent study conducted by dermatologists in Japan quantitatively examined microbiota in follicular skin contents, and providing more evidence that Malassezia spp. fungi may also be present during facial acne episodes in addition to P. acnes.

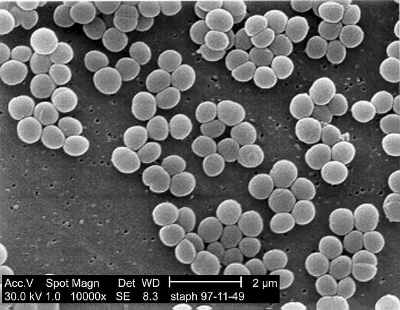

15 untreated acne patients were selected for the study, all of whom had not received previous treatments with topical and/or steroid/antibiotic regiments. A comedo extractor was used to collect follicular contents from inflammatory acne lesions from the cheek and foreheads of patients, and these samples were subject to DNA extraction and subsequent PCR analysis to characterize microbiota species. Staphylococcus and Propionibacterium were found in follicular contents, but interestingly Malassezia spp. fungi were also observed. Furthermore, Malassezia spp. fungi in follicular contents were correlated with inflammatory acne and with content on the skin surface, while Staphylococcus and Propionibacterium were not.

These findings suggest that Propionibacterium acnes may not be the only microbiota skin residents related to acne. While this was not the first paper to point to Malassezia spp. fungi as implicated in acne, these researchers addressed prior experimental method concerns and utilized advanced quantitation methods such as PCR rather than culture-methods.