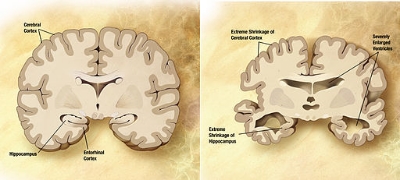

Comparison of a normal aged brain (left) and the brain of a person with Alzheimer's (right).

The gut-brain axis refers to the interplay between the gut microbiome and our behavior. There are a few mechanisms by which the gut microbiome can affect the brain, such as by directly communicating with it via the vagus nerve, by producing hormones or other metabolites that influence brain function, and by eliciting a systemic inflammatory response. This past month researchers Timothy G. Dignan and John F. Cryan, both of the University College Cork, in Cork, Ireland, published a review of the recent advances in the gut-brain axis literature. Many exciting scientific developments have occurred in the past few years, including new advances that connect the microbiome with depression, autism, Alzheimer’s disease, and schizophrenia. Here, we discuss some of those studies and summarizing the review.

Depression: Studies have shown a possible association between the microbiome and feelings of depression. It is not clear, however, if these changes are due to drugs that are being taken. Other studies have shown that probiotics can reduce thoughts of depression, and a separate study showed that eating yogurt improved the moods of oil workers.

Autism: Again, research has shown a correlation between the microbiome and autism, but not any sort of cause or relation with symptoms. Multiple studies in mice have shown that a dysbiotic microbiome can lead to autism like symptoms, and that altering the microbiome can alleviate them. Again, however, there are few mechanistic links between the microbiome and the disease.

Alzheimer’s disease: Very few studies have linked Alzheimer’s and the microbiome. Some studies have seen a broad decline in microbiome diversity amongst Alzheimer’s patients, but decreased diversity is known to be associated with many other phenotypes. Smaller studies on mice have shown some symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as memory loss, can be somewhat reversed using probiotics, but the results are hardly robust and do not necessarily imply a link with Alzheimer’s.

Schizophrenia: Like Alzheimer’s, very few studies have linked the microbiome and schizophrenia. Like all of the above, various associations have been made between the disease and the microbiome, but no strong correlations have been measured. In mouse models of schizophrenia, antibiotics can alleviate symptoms of the disease. In addition, there is evidence that antibiotics can also improve the mental state of humans.

Taken collectively, there is a compelling reason to believe that the microbiome is important to each of these indications, and that it is critical to a healthy mind. It is still early days though, and much more research is needed to prove mechanisms and pathways.