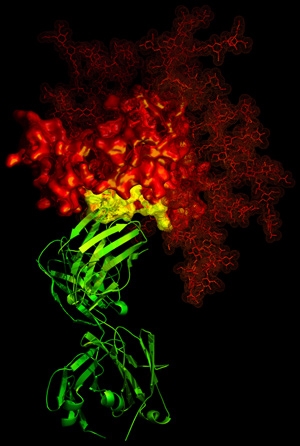

Molecular representation of an antibody (green) binding with an HIV virus (red and yellow).

The viruses that live in our body may be just as important to our health and development as their bacterial counterparts. Unfortunately, testing which ones currently exist, or have at point infected us is expensive, time consuming, and laborious using current techniques. Making matters worse, these techniques, which usually rely on measuring the amount of antibodies against specific viruses that exist in our blood, are often times ineffective when the antibodies are in low levels. Recently though, scientists from Harvard University developed a new technique that can accurately, rapidly, and inexpensively (~$25) screen for the existence of over 200 viral antibodies in less than a drop of blood. They call their technique VirScan, and they published their method last week in Science.

The scientists combined two advanced biological screening tools to create their method: DNA microarray synthesis and phage display. In short, the scientists created libraries of peptides that represented 206 known human viruses, like HIV and influenza, and expressed them on simple bacteriophages. They then combined these bacteriophages with a drop of blood, which itself contains antibodies that combat viruses that someone currently has, or has been infected from in the past. The antibodies that exist specifically bind to the phages that represent a virus. They then eliminate all the phages not bound to antibodies, and measuring what remains gives the scientist an indication of which antibodies were in the blood. This explanation of the researchers’ technique may not satisfy our more curious readers, so those that wish to learn more should definitely check out the paper. When the scientists screened over 500 people using this method, the results showed that most people tested positive on average for 10 viruses (i.e. they had antibodies against these viruses). Interestingly, 2 individuals tested positive for 84/206 viruses. The most commonly detected virus was Epstein-Barr virus, followed by types of rhinovirus (common cold), and adenovirus. Also of interest was that the viral structures differed geographically between continents.

This assay has many immediate implications in many areas. The most obvious is its use as a diagnostic tool for easily screening people for their viruses. In addition though, by discovering which peptides antibodies efficiently bind to, and how those differ between humans, more effective vaccines can be developed that treat more people. Also, it should be interesting to discover how infection with certain viruses influences long term health and chronic disease. For example, were those two individuals that tested positive for antibodies against 84 viruses more, or less healthy than those who tested positive for very few, and whether infection with certain viruses is associated with any chronic conditions.