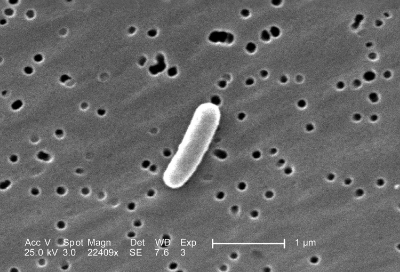

The microbiome of a zebrafish (shown above) was successfully transplanted into a mouse gut.

An article was recently published in Cell that explored how bacteria from various microbiomes colonize in a mouse gut environment. Researchers, including Jeffrey Gordon, introduced microbiota from different habitats to groups of mice. These habitats included human, termite, and zebrafish gut microbes, microbes from human skin and tongue, and communities from soil and marine sediment.

Results suggested that the mouse gut, while selective, provides an environment in which all of the above microbiomes can survive. Results also showed that when cohousing a mouse with an already established normal microbiome alongside a mouse that had a foreign microbiome, the foreign microbiome is not able to colonize in the mouse with indigenous microbiota.

In another experiment, researchers cohoused three mice: one harboring mouse gut microbiota, one with human gut microbiota, and one that was raised in a sterile germ-free environment. Results showed that in the first few days the human gut microbiota colonized the sterile mouse before the normal mouse microbiota was able to, however, after 2 weeks’ time the normal mouse microbiome took hold in all three mice. This suggests that while it is possible for opportunistic microbiomes to establish themselves, the mouse microbiome will eventually fulfill its ecological niche, as it is best suited for the mouse gut environment.

This study helps lay the foundation for future probiotic research because it describes the ability of mice to host a variety of foreign microbiomes, and the necessary conditions to do so.