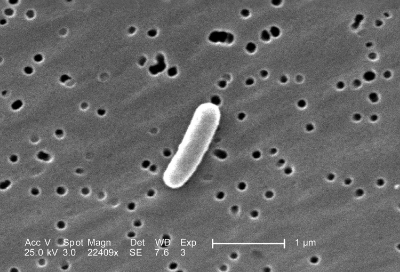

Microbiome sequencing and analysis is at the heart of microbiome science. While established protocols do exist in order to identify the bacteria in samples, there is still a lot of variability between labs, individuals, reagents, analytics techniques, and instruments. This makes comparing data across groups difficult. The microbiome quality control project (MBQC) was carried out in order to determine the sources of variability that exist. During the project identical samples were sequenced by various labs, and the results were compared. The project’s conclusions were published this past week in the journal Genome Biology.

There was a lot of variation from many of the sources during experimentation. Overall, DNA extraction technique proved to be a major source of error. On the other hand, sample storage protocols, such as length of time the sample spent in the freezer, appeared to only play a small role in variability. Another encouraging result was that the the bioinformatics pipelines, i.e. the software programs used to determine the bacteria from the raw data, displayed consistent results. The project also included negative controls that should have contained no bacterial DNA at all, however many labs reported seeing non-trivial sequences. In addition, the samples with known compositions often times had spurious DNA from bacteria that should not have been there. Sometimes the results showed upwards of 7x more bacteria organizational taxonomic units (OTUs) than expected.

This initial MBQC project accomplished two of its major goals, and therefore should be considered a success. First, it demonstrated a need for quality control within microbiome scientists. Second, it helped narrow down the variables that need to be studied more robustly in future MBQC projects. For now though, we must just acknowledge that error does exist in microbiome studies, and to keep that in mind when interpreting results.