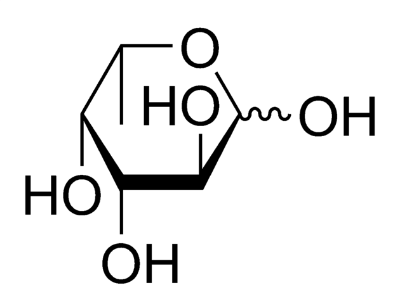

Fucose chemical structure

An estimated 20% of women of European descent are not able to produce mucous that have fucose sugars attached to the ends of their mucin molecules. These women are called ‘non-secretors’, as opposed to ‘secretors’ who can fucosylate their mucins. This rather peculiar genetic anomaly is not appreciated until it is looked at under the lens of the microbiome. Many of the microbiota in the gut feed off the host’s mucins for energy, and the lack of fucose is a major factor in dictating which communities can survive in their guts. During pregnancy the mother’s gut microbiota undergoes a dramatic shift, although what variables are important in determining this shift remain unknown. Last week though, researchers from Finland showed that secretor status was an important indicator in how a women’s gut microbiome shifts during pregnancy. They published their results in PLoS ONE.

The researchers sampled the gut microbiome of 71 women throughout their pregnancy, and compared it to the secretor status, as determined by genetic testing. In the first trimester of pregnancy each women, secretors and non-secretors alike, had similar diversities in their gut microbiota. However, by the third trimester the non-secretor’s gut microbiomes were much lower than their secretor counterparts. When the scientists measured specific phyla, they observed an increase in the abundance of Actinobacteria in the secreting women, and an increase In the abundance of Proteobacter in the non-secretors.

The changes in gut microbiota in these women may be very important to the microbiome of the infant that is born to them. As an infant passes through the birth canal he or she is exposed to the mothers’ vaginal and gut microbiota, and these bacteria serve as the initial populations that seed the infants’ own guts. In addition, some of these specific bacterial populations, such as Proteobacter, are implicated in diseases like IBD. If these bacteria persist in the mother after birth they may explain the onset or increased risk of some of these diseases.