On this week's podcast, we talked with Kristina Campbell from Gut Microbiota for Health. Kristina had recently traveled to three conferences around the world so we talked with her about what's going on in the field and the most recent breakthroughs in the field. We also announced that we set up a voicemail for callers to call-in and ask us questions or leave comments for the next episode of the podcast. The number is 518-945-8583 and we hope to hear from you with any questions, simple or complex, that you want us to answer on the podcast.

Listen here:

And listen here on iTunes and Stitcher.

See below for more detailed show notes:

The episode begins with a few recent news stories:

(2:57) The Obama administration announced a $1.2B plan to fight antibiotic resistant bacteria. Read more.

(5:00) A group at the University of Nottingham used a 1000 year old recipe to kill MRSA and it was very successful. Read more.

(7:13) The Massachusetts Host-Microbiome Center is being created by a $4.8M grant from the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center. Read more.

In the conversation with Kristina (@bykriscampbell on twitter and read her personal blog here) we discussed:

(9:29) Gut Microbiota for Health, the website that Kristina writes for. Check out the site.

(10:46) The Keystone Symposia that she attended. Link.

(12:48) Skip Virgin’s keynote address discussing the virome and IBD. Read our blog post about his paper on the subject.

(15:40) The Gut Summit that she attended in Barcelona. Link.

(17:24) Maria Gloria Dominguez Bello’s work on c-sections. Watch a replay of her talk from the Gut Summit.

(19:38) The Experimental Biology conference in Boston. Link.

(20:13) Emeran Mayer’s work using fMRIs. Read about Dr. Mayer.

(23:10) Fecal microbiota transplants

(24:10) OpenBiome

(30:35) The milk microbiome

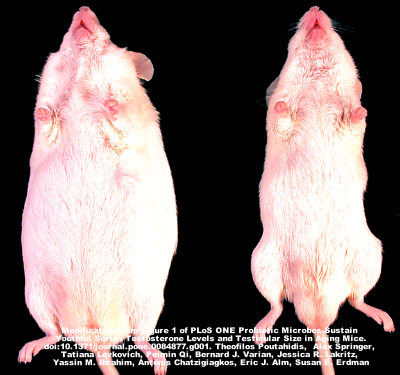

(33:58) Obesity and the microbiome and (34:50) research on using FMTs for treating obesity. Link.

(41:35) After the interview with Kristina, we again discussed the NCAA tournament and how our picks before the Round of 32 are faring.

The next podcast will be with Justin and Erica Sonnenburg, scientists at Stanford University School of Medicine. Leave a voicemail for us at if you have a question for Erica and Justin about the impact of diet on the microbiome or anything else microbiome related.