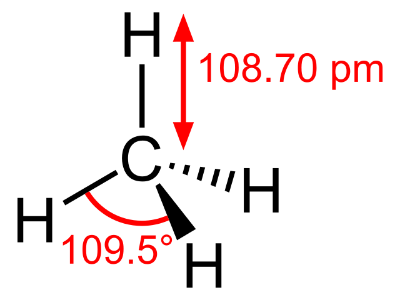

Methane (above) is produced by Methanogens, which are increased in the guts of healthy individuals compared to those with diarrheal IBS.

IBS affects somewhere around 11% of all humans. It is not known exactly what causes the disease but it is characterized by a low grade inflammation in the colon which can manifest itself as cramping, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and overall abdominal discomfort. Many scientists now believe this is a microbiome mediated disease that is caused by some sort of dysbiosis in the gut, unfortunately efforts to characterize exactly what differences occur in IBS individuals have not been successful. A new article published last week in Nature Scientific Reports describes newly discovered differences in butyrate and methane producing bacteria in the guts of people with IBS.

The scientists sequenced the microbiomes of 66 healthy controls and 113 folks with IBS, at two time points 1 month apart. They discovered that IBS patients had higher amounts of Bacteroides and lower levels of Firmicutes than healthy individuals, as well as an overall lower microbiome diversity. In addition, there were no major changes to either group’s microbiomes over the one month measurement window. Interestingly those people with diarrheal IBS had much lower levels of methanogens than healthy controls, and those people with constipation IBS had higher levels of methanogens than healthy controls. Methanogens convert hydrogen gas to methane in the gut, and this study revealed a link between methane production and gastrointestinal (GI) transit time. Finally, the researchers determined that diarrheal IBS patients also had much lower levels of known butyrate producers. Butyrate, a short chained fatty acid (SCFA), is associated with improved GI permeability and overall GI health.

This study described a few important insights in IBS and the microbiome. These insights, such as the metabolic differences between bacteria in healthy individuals and those with IBS may be important to future therapeutics to treat this disease. For example, perhaps folks with IBS could eat a lot of fiber and in the hopes of increasing the amount of butyrate in their guts. Of course, the observed difference is only an association at this point, but other studies have suggested an increase in fiber can help relieve symptoms of the disease.