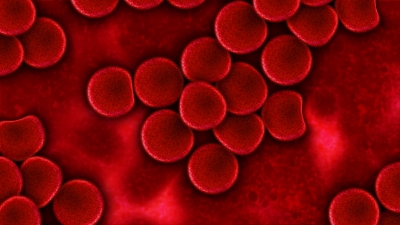

Red blood cells in plasma

In general, a significant amount of attention is placed on microbiome communities in our gut and skin, and their respective relationships with other tissues in our bodies (the brain, for example). However, the cells and fluids that are essential to our survival, such as blood, may also play an important interactive role with our microbiome. This relationship is demonstrated in a recent study aimed at identifying bacteria found in standard blood-packs used for blood transfusions, and examining bacterial distribution and distinct strains present in blood-plasma and red blood cells.

Transfusion-transmitted infection remains the leading cause of post-blood transfusion mortality and morbidity even though these risks have declined significantly in recent years. As the name suggests, transfusion-transmitted infections result from the introduction of foreign pathogens to a patient’s blood stream via a blood transfusion. However, previous research has identified a significant discrepancy between post-transfusion infection rate and bacterial growth observed in the blood pack from which the transfusion was received. Specifically, a 16.9% rate of post-transfusion infection (11.8% under more reserved transfusion methods) is observed. However, data from standardized bacterial screening protocols indicate that less than 0.1% of blood packs actually contain bacterial growth.

Previous literature examining bacteria translocation into red blood cells concomitant to epidemiology data related to gum disease suggest that the oral cavity, or mouth, can serve as a viable access point for bacteria to enter into the blood stream. Furthermore, conventional methods used to screen for bacteria presence in blood packs does not account for bacterial adherence to red blood cells. To address this discrepant data and literature-supported suppositions, a twofold approach was taken. Researchers sought to determine if known oral cavity bacteria strains are found in donor blood packs and whether or not these bacteria adhere to red blood cells.

Blood was drawn from 60 healthy study participants and subjected to specific fractionation procedures to separate red blood cells from plasma. Red blood cell and blood plasma suspensions were subsequently plated on cell culture dishes and incubated for 7 days under specific conditions to allow researchers to isolate bacteria from red blood cells and identify the strains. General bacterial growth was evident in both red blood cell and blood-plasma dishes. Of the 60 plates corresponding to 60 patients, marked growth was observed in 35% of the red blood cell cohort and 53% of the blood-plasma cohort. DNA amplification of known bacteria found in the oral cavity was then used to determine the specific bacterial strains that were incubated on these plates. Various aerobic and anaerobic strains were identified and it was interestingly noted that these bacteria are undetectable using standardized bacterial screening techniques.

These findings certainly have major implications for clinical diagnosis of bacterial contaminants found in blood packs. In particular, detection capabilities of diagnostics must be improved, as it turns out that there may be significant amounts of bacteria in blood packs than previously realized. This study also illustrates that bacterial communities are mobile and are not limited to gut, skin, mouth, vagina, and other tissues we normally associate with the microbiome. The ability to adhere to red blood cells certainly gives microbiota populations a much more dynamic range of influence in our body’s respiratory, immunologic, and overall regulatory processes.